Survival Guide for the Next Recession

By Arie van Gemeren , CFA – Principal @ Rising Tide VC

As a former public-stock market “guy”, it’s been interesting to make the transition to venture capital and observe connections between what happens with the “big boy/girl” stocks and the early-stage world. After all, what happens with interest rates and real estate and EXXON MOBIL stock and an early-stage cloud computing startup are actually linked, whether you can believe it or not. Everything comes down to the fundamentals of the economy itself, and what quickly transfers through to a public security will (surely?) eventually find its way through to a startup.

But the ways in which it happens will be different, and that’s the intent of this post. While a hedge fund or long-equity manager has to post mark-to-market losses to a public stock portfolio quickly, the “effects” of a bear market (broadly defined as a decline of 20% or more in public stocks) on a private security portfolio will take longer to be felt. But the effect is going to be there, nonetheless. What, then, are the risks for investors and entrepreneurs to keep in mind?

They boil down to these:

1- Need for additional financing (availability of capital / valuation destruction / effect on employees)?

2- Un-accommodative business environment

3- Hostile M&A Environment (true or no?)

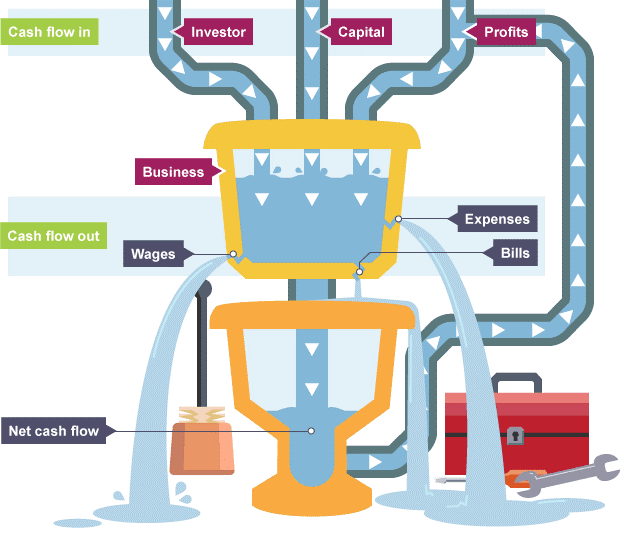

First off – what does a “recession” mean, broadly speaking – and how does it trickle down to early-stage companies. A recession can come in various forms, and broadly speaking the ones you really need to fear are those driven by some major economic imbalance (like debt buildups prior to 2008) and/or ones driven by a huge, exogenous risk (like the Arab Oil Embargo or the start of World War 2). These, though, are hard to predict. The more common is what’s called a “Cyclical Recession” which just means that the economy goes through a cycle and inevitably goes through a downturn. The reasons why are typical of a build-up and then bust – businesses take on debt, they finance growth, and eventually growth can’t be found at the same levels that the market predicted, and so therefore it goes through a cyclical slow-down before launching again on growth. These are usually softer in nature (the magnitude of the market downturn) but still not fun for anybody involved.

But what does this mean from a macro level for the market environment? First off, it could trigger a “risk-aversion” marketplace for investors themselves, which bodes poorly for money to be poured into early-stage tech startups. Hence, to point 1 above, the results may be that venture capitalists themselves struggle to raise high-risk, early-stage investment funds. Should VCs fail to raise subsequent funds, the availability of capital could become scarce, which may impede follow on financings and subsequent capital raises.

This can be dangerous for startups. In my view, there are two (well there’s more, but for this discussion let’s focus) sorts of startups. There are those that binge on VC jet-fuel capital to fuel a massive jump for scale, but in doing so post huge losses and require follow on financing to continue expanding upward and onward. These companies (we have seen several go public recently, and others are well-known private companies) need money to keep growing. If the money becomes scarce, it means that terms could become nasty, which given anti-dilution measures could pummel the value of common stock AND make incentivization of employees even more difficult.

The second type of start-up should (in theory) fare better, which is one that has taken a more measured approach to growth and is posting more profit (and fewer losses – or at least, less losses for the sake of achieving scale) and might be able to batten down the hatches and ride out the storm. The availability of capital – to my mind – is directly related to what’s going on more broadly in the markets and can make or break a company going through this period.

In addition, in a sustained market downturn with scarce capital, VCs are likely to also invest more conservatively, and demand larger stakes in return for putting their money to work. This has the effect of harming valuations and forcing founders to potentially give up more equity to raise capital (and if you’re feeling the cash crunch and the choice is your equity or your company, I think we know what usually will happen). And while this can be harmful to valuations, it has the doubly nefarious effect of also impacting a start-up’s ability to incentivize employees. Down-rounds (a round of financing raised at a lower valuation than the last one, which would undoubtedly be more common in a protracted downturn as described immediately before this) can cause employee’s option packages to be worthless as the stock’s value goes below their strike price. This, in turn, can cause employees to look elsewhere or (perhaps even worse) stop working as hard or be incentivized to build as their own compensation is zilch.

All of this leads to a second, very serious risk for start-ups to consider. In a sustained market downturn, major companies may themselves decide to ratchet back on discretionary spending and focus on protecting themselves. This means that any start-up whose core proposition as a B2B company that isn’t directly additive to the bottom line for the end-buyer may find the buyers themselves disappearing. Even those with a compelling value-proposition may find themselves without a buyer. This, to my mind (as an investor), speaks to investing in companies whose technologies or services are truly indispensable (from a defensibility AND a growth prospective standpoint), but it also means that anything which is experimental or more of a luxury to have may lose some or all-of their revenue. This, coupled with the previous observation that capital markets may dry up, would mean that many start-ups may not survive the coming winter.

Which leads to the third point. Some – myself included – might posit that with market valuations down, and an abundance of weak businesses and startups out there with interesting IP, that you would expect the M&A environment actually to heat up. After all, everybody knows – buy low, sell high – right?

I think this may be right in a narrow, focused bear market. For example, if assets in one sector are trading massively below value, then buyers may swoop in (Private Equity, for instance, recognizing an opportunity). But if it is a broad-based bear market, the results might look quite a bit different. Companies may – again – be more interested in protecting themselves and conserving cash. True, the major acquirers with huge war-chests of cash might come out and buy businesses at a discount but remember too that if a start-up is being slammed by points 1 and 2 above, the valuation is surely going to take a massive hit as well. It might provide a nice “soft-landing” for the team, but the economics will surely not be greatly advantageous.

The major point here, though, is that “timelines to exit” will likely be extended. This may create headaches for VCs who are trying to raise subsequent funds (as liquidity is highly prized by all), and if you couple that with a rough market environment and difficulty of raising capital anyways, it could exacerbate the pain in point 1 above and become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

All of this is to say – it’s extremely difficult to predict a bear market. People have been predicting one pretty much since the end of the last one. They’ve been wrong – really wrong – for almost a decade. It’s impossible to predict when the next one will strike. Some say we’ve been at this bull now for 9+ years, surely the time is nigh. It is true that by this standard, we should almost be there. However, time is not the best way to predict a bear market – some bulls last a few years, some last much longer – and the underlying reason for a crash must have an actual economic rationale.

So what to do? It’s hard to say. While the party lasts, the VC-fueled growth and scale narrative makes sense and your fund (or company) may underperform your peers if you don’t get on-board. On the other hand, that narrative will likely crash and burn in a serious market downturn, in which case technology businesses which ran themselves more conservatively and grew at a steadier pace (but disappointed investors who have gotten used to 500%+ growth YoY) will likely shine and look a lot better.

In other words . . .

As an investor: we think it’s good to be diversified across industry verticals and sectors, across both technology and healthcare (as we do) and to invest in calm, able and steady entrepreneurs who are not obsessed with ego or quick growth, but in building lasting and sustainable businesses.

As an entrepreneur: I would focus on having the capacity to massively scale down your burn-rates, on building sustainable business relationships with a diversified group of end businesses (if you only sell to one or two tech companies that are themselves not super strong, I’d be worried – very worried) and if at all possible understand your current investors and their capacity or plans to sustain or support your business in a protracted market downturn. In other words – if your lead doesn’t have a new fund raised right now and their existing fund doesn’t have enough capital reserved for follow on financing, you could find yourself in a harsh situation in the dead of winter. Don’t be that guy / gal, as it won’t be fun! Plan ahead and contemplate worst-case-scenarios.